Beliefs

We all hold beliefs about what we think is beneficial for us and what might be harmful. The question is, do these choices truly support our well-being as individuals? Could some of these ideas lead us in the wrong direction?

A common narrative in many techniques is the idea that pain, dysfunction, or injury in the body are caused by tight tissues that need to “be released”. The belief or experience of stiffness often leads to the desire to choose something that can alleviate the feeling of tightness. Thinking that we can solve a problem with a single trick and assuming that’s the root cause is problematic in itself because the body doesn’t function that way. Our health is influenced by multiple interconnected factors—biological, psychological, and social. What we need is often different from what we want to do. For example, I might want to eat pizza every day, but that’s not a good idea because, after a few months, you might end up looking like a blob of dough.

Feeling stiffness isn’t the same as actually being stiff. It can be something we assume we are because someone in the past has given us this label. There is significant individual variation in the range of motion in our joints throughout our lifespan. Additionally, there can be changes in an individual at different points in the day. How you move when you wake up is very different compared to how you move in the evening after two glasses of red wine. Same tissue, but different factors have influenced it.

The feeling of stiffness can be caused by factors such as a lack of physical activity, lack of sleep, fear of movement, inflammation, or other mechanisms like immune system regulation. The ability to access a larger range of motion (increased flexibility) is influenced by several factors, with one of the key aspects being a shift in sensory acceptance. This means that it’s not necessarily the local structures, such as muscles or tendons, physically gaining more length, but rather the brain adapting to and accepting the new range as safe and manageable. This process involves changes in neural signalling and sensory perception, where the brain reduces its protective mechanisms, such as tension or discomfort, allowing the body to explore and utilise the extended range. Additionally, factors like consistent practice, improved motor control, reduced fear of movement, and relaxation of surrounding tissues can further contribute to enhanced flexibility.

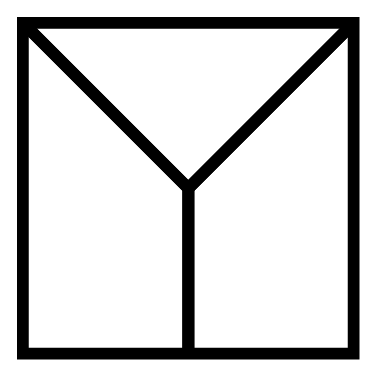

Another problem with the narrative about “opening the body” is that we totally forget to think about that it occurs a contraction and expansion around the tissue. If there’s a widening in one direction, it will inevitably result in narrowing on the opposite side. It’s physically impossible to widen both sides simultaneously. I often hear instructions in yoga or movement practices that say things like “keep both sides open.” While I understand the intention behind these cues and the idea that the sensations might feel pleasant or balanced, it’s important to recognise that what we feel and what is actually happening in the body can be very different. Sensations can be deceiving, and our perception doesn’t always align with what’s actually is happening.

Let’s set aside arguments based on exercise physiology and instead explore the concept of “opening the body” through the lens of language and placebo effects. Certain words have a powerful, almost magnetic appeal, evoking positive emotions simply by hearing them. Words like restart, restore, open, rinse away, and unlock carry a sense of renewal and transformation, suggesting the removal of negativity and the retention of only the good. In contrast, words like close, stuck, or insulate evoke a sense of restriction or that something undesirable is happening. This contrast highlights how language can shape our perceptions and influence our experiences, even in the context of movement. Have you ever heard a yoga class use phrases like “lock your hips” or “close your body”? In the yoga world, it is common to use backbends as a way to “open the spine,” symbolising both physical and emotional liberation. Backbends are celebrated not only for their ability to improve spinal flexibility but also for their symbolic representation of breaking free from constraints and embracing openness. While backbends may create a sensation of openness in the chest area, this feeling is not directly related to the heart itself. The heart is securely protected within the ribcage, making it very difficult to manipulate directly from the outside—a reassuring fact that ensures its safety.

Assuming that you can equate and transfer the philosophy of yoga directly to what happens in physical movement isn’t helpful, as it oversimplifies the complexity of both practices. Yoga philosophy often delves into mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions, while movement practices primarily focus on biomechanics and physical sensations. While there may be overlaps, treating them as interchangeable can lead to misunderstandings about the unique benefits and intentions of each discipline.

Many of the things we think or believe are not entirely true. Our minds are filled with assumptions, interpretations, and narratives that may feel real but don’t necessarily reflect reality. This is a reminder to approach both physical practice and mental processes with curiosity and critical thinking, questioning what we perceive and being open to the possibility that our understanding might be incomplete or flawed.

There is no prerequisite for exercise. You don’t need to open, release, or foam roll any areas before you start moving. As Nike says—just do it.

//Magnus Ringberg